“Thou’art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell…”

– John Donne, on Death

Our house is 35 years old, and it groans. Doors stick, the ceiling peels in thin, papery layers, and a stubborn draft whispers that the insulation has given up the ghost. It’s no longer energy efficient; it’s a tired old structure. We talk about what to do. I mention the nuclear option: demolish it and build anew.

The thought brings a flicker of sadness. We have memories here. This is our home. But the house is inanimate. It has never loved us back. And so, the idea of its end, while poignant, doesn’t shatter us.

But when a living being dies, even a beloved pet, surrendering peacefully to old age, it is a different universe of loss altogether.

Death is the great certainty that terrifies us. As the biochemist Nick Lane writes, it is “programmed into the very fabric of life.” We know it’s coming for us all. Yet this certainty is wrapped in mystery. What happens, really, when we die? Where, precisely, does life go? And what is the root cause of this inevitable end?

Lets dare to look closer.

Part 1: The great deconstruction

What happens to a body after death? It’s a question that often makes us flinch, but the process is not one of horror; it is one of return.

When life stops, the body’s bustling metropolis of systems shuts down. The heart, that relentless pump, ceases its hard work. Without circulation, the body’s warmth begins to seep away, bleeding into the ambient air until it reaches room temperature. Breathing stops. No more oxygen comes in. The energy currency of our cells, ATP, can no longer be minted.

Without energy, the muscles, which need power to relax, lock into a final, silent protest: rigor mortis. When they eventually release, the last vestiges of the body’s waste are expelled. The skin, no longer flushed with blood, grows pale and shrinks.

And then, the second life begins. Our bodies are not just ours; they are home to trillions of bacteria, ancient tenants residing mostly in our gut. While we live, our immune system keeps them in check. When we die, the resistance ends. The tenants take over the house. They begin to consume the body’s organic resources, releasing gases as they work. This odour is a dinner bell, summoning a host of scavengers to a final, riotous party. What’s left is slowly broken down, until only the hard parts bones and teeth remain for a slower, more patient decay.

The body is unmade. But has life truly left?

Part 2: The decider

If a cell is the fundamental unit of life, then surely death is not a single moment, but a cascade of tiny deaths. This is where the story gets truly profound. Billions of our cells are born and die every day, even before we are born. The very spaces between our fingers and toes were carved out in the womb by cells programmed to die.

So when does life finally move out? Perhaps when the very last cell dies.

To understand this, we need to understand how a cell dies. Most cells don’t just break down; they undergo a “controlled demolition.” Inside each cell is a demolition crew, a family of enzymes called caspases. When activated, they dismantle the cell from the inside out, neatly and without disturbing the neighbours.

But who gives the order? Who pushes the plunger on the dynamite?

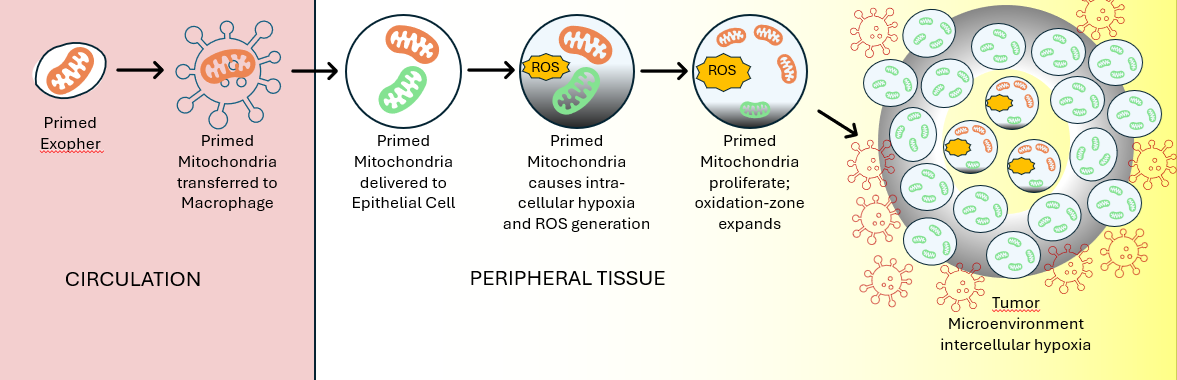

The order comes from the cell’s power plants: the mitochondria. When a cell is under stress, its mitochondria release a protein called cytochrome c. Inside the mitochondria, this protein is a loyal worker, essential for generating energy. But once it escapes into the cells cytoplasm, it becomes a messenger of death, activating the caspase crew.

The mitochondrion, it seems, not only decides how energetically a cell lives, but also precisely when it must die.

Part 3: The ghost in the machine

If death is programmed into us, what good does it do? Why would nature build such a self-destruct sequence into its creations?

One powerful idea is that death is a feature, not a bug. It’s a mechanism for scheduled obsolescence. An organism’s primary purpose, from an evolutionary perspective, is to reproduce. Once that job is done, the body’s warranty expires. Gerontologists call this the “essential lifespan”; for humans, it’s around 45 years. Beyond this, we begin a progressive decline.

The diseases of old age, Nick Lane argues, are not the real disease. They are merely symptoms of the underlying condition: ageing itself. And the root cause of ageing, many believe, is the slow, inexorable decay of our mitochondria. The “wear and tear” of life is the accumulation of damage in these ancient powerhouses. As they falter, they leak more and more “reactive oxygen species” sparks flying from an overloaded engine. These sparks damage our DNA, leading to a system-wide failure that we call old age.

And what is cancer, one of our most feared killers? It is the opposite of this elegant, programmed death. Cancer is a cell that has ripped up the self-destruct memo and is screaming, “I will not die!” Its a rebellion against the mitochondrial order.

The life that never ends

We come back, again and again, to the mitochondria. In death, our bodies are unmade, the great house of our life demolished. Through reproduction, we pass on a new blueprint – half of our nuclear genes from each parent.

But something else is passed on, something more ancient and unbroken. A mother passes her mitochondrial DNA to all her children, whole and intact. It is a thread of life that has been passed down in a continuous, direct line from the very dawn of complex life.

Your body will die. But the mitochondria inside you are part of a lineage that may be billions of years old. They are the true survivors. As the poet Rabindranath Tagore wrote, they exist “jibon moroner simana chharaye” beyond the bounds of life and death.

Perhaps this is what John Donne foresaw centuries ago. Perhaps, in the eternal life of our mitochondria, we see the very thing that makes “Death… die.”